CEDAR CITY — Even as fentanyl floods the market at 50 cents a pill and demand skyrockets, Iron County law enforcement battles bureaucratic red tape just to save lives.

Officers, once able to easily acquire the life-saving antidote Narcan from the local health department, now must navigate state channels in what many are calling a “wait and see game.”

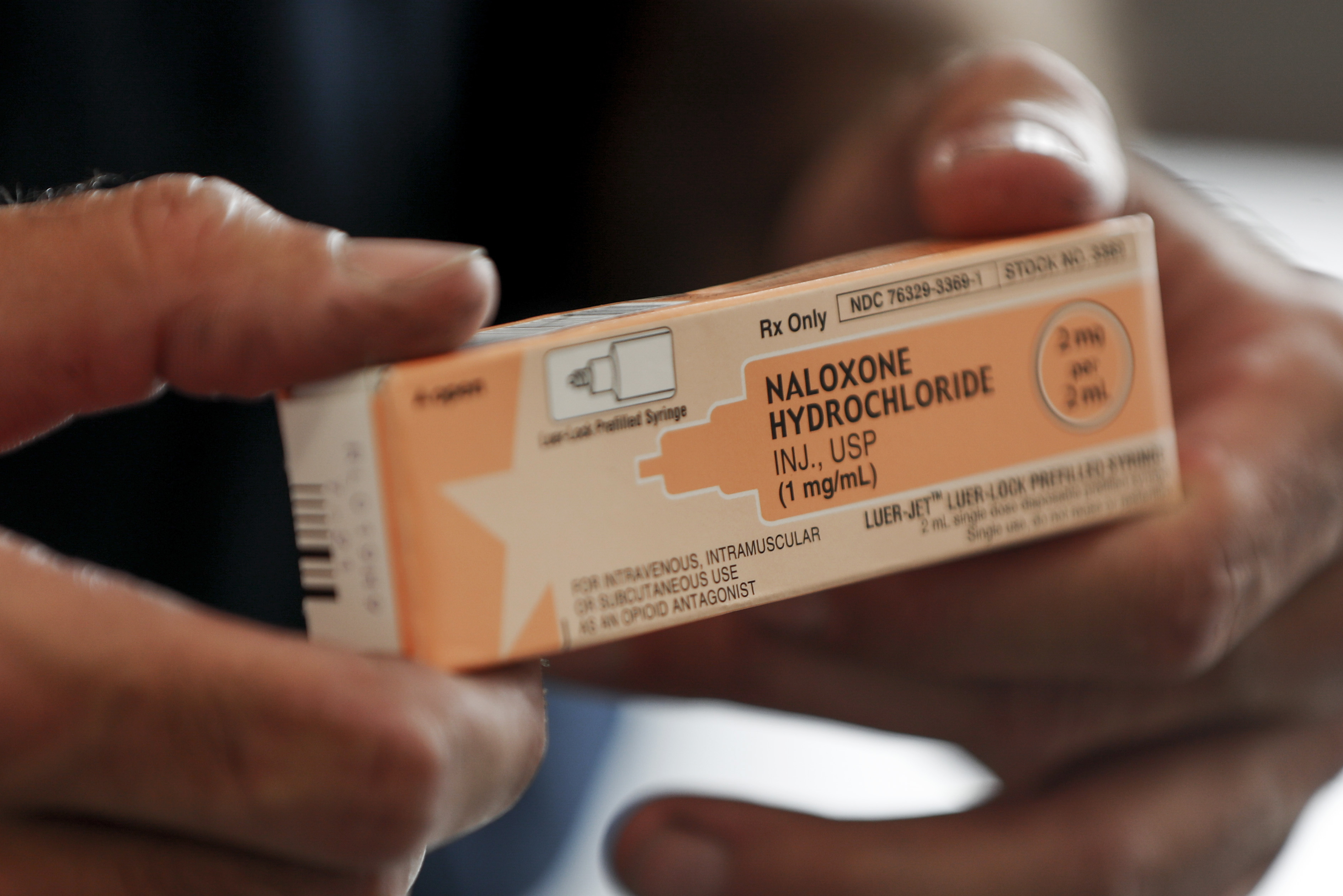

Narcan, also called naloxone, is a life-saving medication used to quickly reverse opioid overdose. It can be given through a nasal spray, a shot into the muscle, or directly into a vein, and usually starts working within minutes.

Due to its effectiveness and easy use, Narcan has become a vital tool for law enforcement in fighting the opioid crisis. It is also available over the counter allowing anyone to carry it.

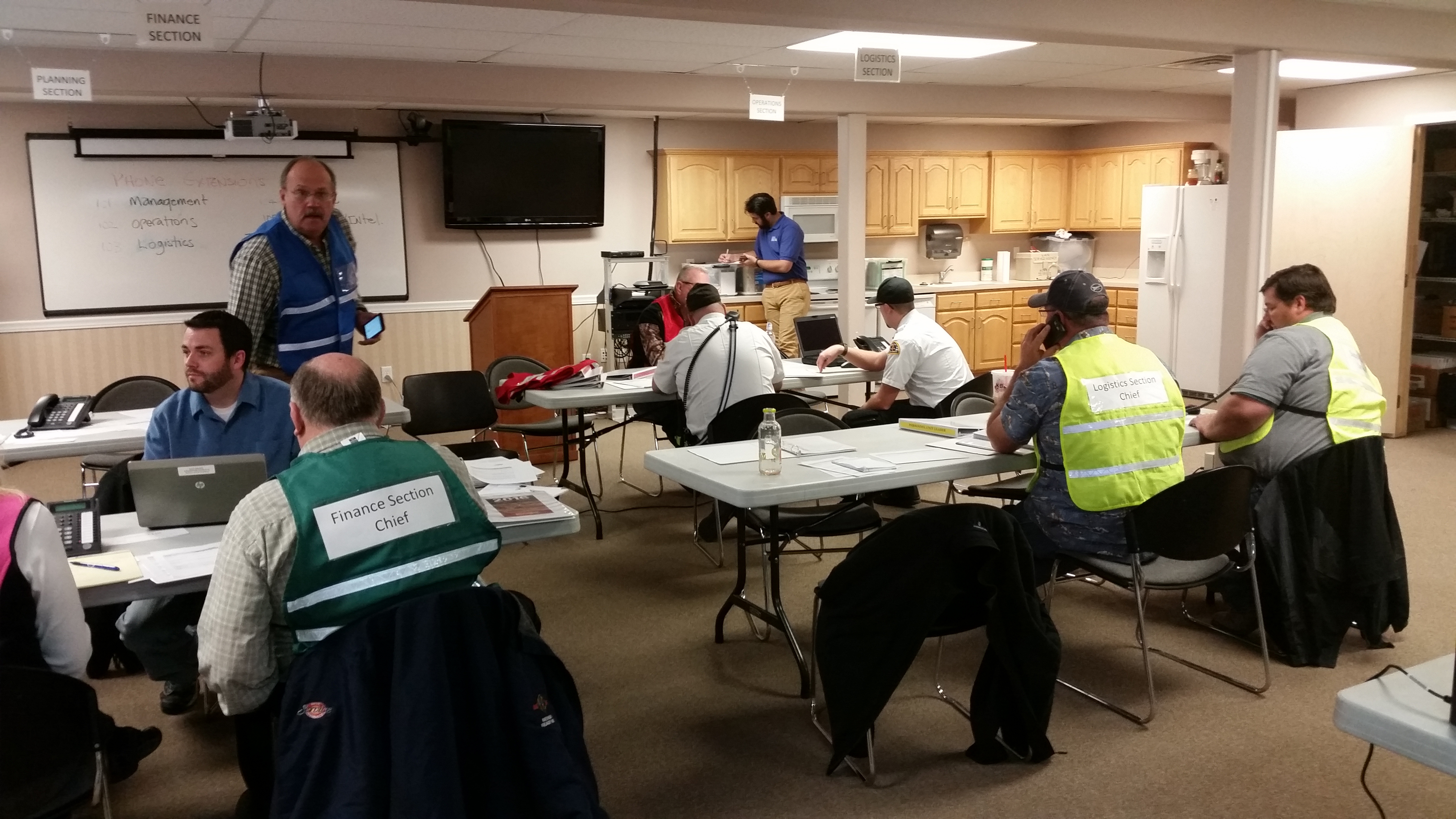

For the past 18 months, Iron County Emergency Management Director George Colson has been obtaining Narcan for free for local first responders from the Southwest Utah Public Health Department.

“It was really easy to get. I would just walk in and tell them what I needed and they would give it to me,” he said.

During this time, the local health department employed a health educator to instruct law enforcement and the public about Narcan. She also arranged for and distributed the medicine at no cost to officers or residents who requested it.

The funding for this position came through the Utah State Department of Health and Human Services via the Opioid Data to Action grant, which originates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In January, the funding for the position ran out. Additionally, the CDC reduced the new grant money by more than $1 million and changed the requirements to apply.

This eliminated the chances of SWUPHD receiving any more money, according to public information officer Dave Heaton.

As a result, the health educator position for SWUPHD was eliminated, halting the supply of Narcan through the local health department.

However, Colson only received the notification about the change a little more than a month ago. By then the position was already gone and the letter provided no guidance or direction on how he should move forward.

After reaching out to several legislators and state leaders for two weeks Colson finally learned he could go online and fill out a state form with the Department of Health and Human Services to apply for the Narcan kits.

He made his first order requesting 200 doses more than two weeks ago, however, and still hasn’t received anything.

“The site confirmed they got my application but I still don’t know if they’re going to give it to me and, if they do, when I’m going to get it,” Colson said.

Colson’s last visit to SWHD to pick up Narcan was around August. He estimates that he picked up about 200 doses during that visit, which he then distributed to local law enforcement.

“It just depends because sometimes I will pick up that much, and some departments still have some but others run out,” Colson said. “And I don’t know how long I’m going to have to wait now to get more. Or for that matter, if I’m even getting any.”

It often takes two doses to revive someone from an overdose. With each dose priced between $40 to $75, local law enforcement is concerned about accessing the drug when needed.

Officers typically carry two to four doses at all times. Considering this, the potential financial strain on each agency having to purchase Narcan themselves could quickly become overwhelming, Cedar City Police Public Information Officer Justin Ludlow said.

“If our department has to pay for their own Narcan, we won’t be able to carry as much as we have before,” he said. “It’s just too expensive and small departments like we have in Iron County do not have the budget to pay for it all the time.”

In addition to not knowing whether he’ll receive Narcan from the state and how long it’ll take, Colson’s also concerned about whether DHHS can keep footing the bill for it.

But despite the reduction in funding in the grant money, DHHS Public Information Officer Miranda Fisher said it shouldn’t affect the agency’s ability to supply the Narcan kits.

“It should still be easy for counties to receive naloxone,” she said. “The program has not changed. Local health departments and counties can request naloxone at any time to be distributed in their communities.”

Colson worries though that the funding will run out and he will be unable to get what the officers need. He is also concerned that it may take longer and in the meantime, officers may run out.

“I knew when I went into the local health department I would be able to get what the officers needed,” he said. “I never worried about whether it would be there. The overdoses these officers are being called on have risen exponentially in the last four years and I want to make sure they have the tools they need to deal with it.”

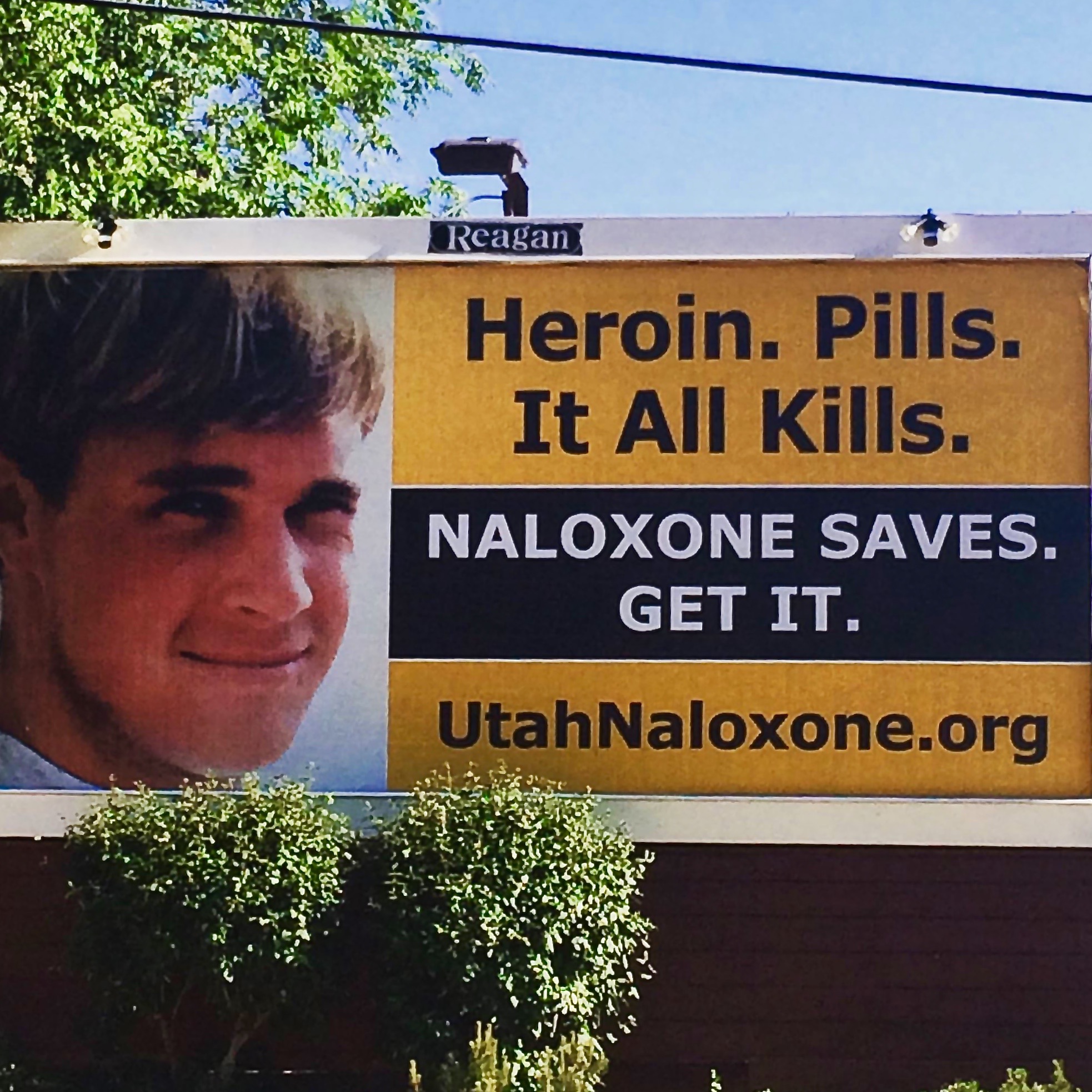

Like the rest of the country, Iron County is not immune from the opioid crisis now ravaging America’s city streets. As the county’s emergency management director, Colson works closely with law enforcement and knows what they are up against.

“The bottom line is, if those officers don’t have Narcan to carry when they need it, people are going to die,” Colson said. “And the reality is that these agencies cannot afford to buy what they need. It’s too much and it’s too expensive.”

Iron County Narcotics Task Force Commander Zac Adams said he has seen more drugs on the streets of Iron County in the last two years than ever before. The drugs are easy to get and they’re cheap to buy, he says.

“The drug business works like every other business and supply and demand drive the prices,” Adams said. “And there is such a huge supply and demand of drugs out there on the street, fentanyl is now 50 cents to a $1 a pill. Compare that to $7 to $15 a pill a few years ago.”

There is also an increased risk of people inadvertently consuming other drugs laced with fentanyl. Even purchasing marijuana from street dealers poses a potential danger.

“We haven’t personally seen marijuana laced with fentanyl but that doesn’t mean it’s not out there. A lot of what we’re seeing though is straight powder and they use that to lace the other drugs,” Adams said.

Iron County, a major route for drug trafficking, ranks second in the state for drug busts originating from Interstate 15, Iron County Sheriff Ken Carpenter said. This indicates a significant influx, outflow, and transit of drugs through the area, a trend law enforcement anticipates will worsen.

Recent data from the Cedar City Police Department shows the agency has had an average of about six overdose incidents a month since August 2023, Ludlow said. Iron County Sheriff’s Office’s records show their agency responded to five overdoses in 2023.

Those numbers, however, may not show the full picture, Carpenter said.

According to the sheriff, the incidents are logged based on the information provided by dispatch operators. For example, if a call comes into 911 as a domestic violence case, it will be recorded as such. However, that same incident may also have an overdose involved.

These cases won’t be automatically classified as overdoses unless officers manually include a secondary code in the system indicating an overdose.

“So you would have to pull every individual report to find out which ones there were overdoses involved,” Carpenter said. “I know our agency responded to more overdoses than that last year.

In light of the bureaucratic obstacles encountered by Iron County law enforcement in obtaining Narcan, there remain concerns within the community and law enforcement regarding heightened risks amid the surge in opioid-related incidents.

Efforts to streamline processes and ensure timely access to life-saving resources remain crucial, Carpenter said.

“It’s important that this process is streamlined and that we can access the tools we need easily and quickly,” he said.

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2024, all rights reserved.